There’s no doubt about it – Bhutan is very different. I’ll begin by trying to set the scene.

It is a small country, about half the size of Indiana, about 200 miles from west to east, and 100 miles from south to north. In that latter direction, it rises from a low point below 100 m above sea level to a little over 7,500 m. That makes it pretty steep! The southern border is on about the same latitude as Laredo, Texas; the climate is tropical, yet the northern border is clearly a hostile mountain environment. Almost three quarters of the land is forest, and a mere 2.5% is cultivated.

Bhutan is sparsely populated, and although much of the terrain is uninhabitable, even the small capital city, Thimphu, feels very empty and quiet. The central road junction is easily controlled by a uniformed policeman, a role that has been re-instated following a brief experiment with a set of traffic lights. The population preferred the human touch, and in a country where politics are guided by the principle of Gross National Happiness, their preference was duly noted and acted upon. Western politicians please note!

So Bhutan has no traffic lights whatsoever – nor for that matter does it have a single ATM! Furthering the sense of extraordinary, I could tell you that it is illegal to sell tobacco in Bhutan, that the national sport is archery, that men wear a skirt to work, and that television has only been permitted since 1999. The national dish is chili – no, not as in a seasoning, but as a plate of chilies! Rice is a major crop, but even that is red.

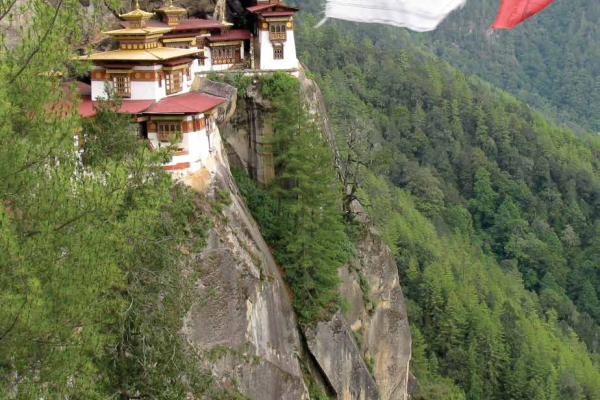

The people are actively religious, with some 75% being Bhuddist and the remainder mostly Hindu. In practising their religion, they will try to visit pilgrimage sites if they can, and we too made our journey to Taktsang Monastery, as part of our acclimatisation program. This monastery (also known as the “Tiger’s Nest”) is something every visitor should aim to see. It can only be reached by a steep climb of a couple of hours, but the spectacular setting and the distinctive interior amply repay the effort. The monastery is not old, but has been restored as faithfully as possible following a serious fire. The site is old, however, and is supposed to be the location where the guru landed his tiger when flying in to bring Bhuddism to Bhutan.

My visit to this singular country was as part of group organised by the Alpine Garden Society, so I should also write something of the plants that we saw. And did we see some plants! Being a mountain and flower lover rather than a botanist, I won’t attempt a detailed report but I will give you a look at some of my favourites. We did see some 800 species, so you may well be glad of this approach!

Before leaving the tree-line below, the stars of the show must be the cypripediums. But for our knowledgeable local guide, we would have walked past the first, the dainty and diminutive Cypripedium elegans, but there was no way we would miss either the relatively common C. himalaicum or the much less common C. tibeticum.

As we got higher, we began to see plants more typically associated with the word “alpine.” Primulas there were in quantity, from the tiny to the substantial. In the latter category, Primula hopeana, similar to P. alpicola, was abundant wherever there was ample moisture, and in places it stained the hillsides yellow, and was visible from a considerable distance and P. tibetica grew nearby, at the opposite end of the size spectrum. Higher up, pride of place was taken for me by Primula calderiana subsp. calderiana, which was never common but made a spectacular clump when found. On steep earth banks, moistened by the monsoon rains but perfectly drained, was the beautiful powder-blue P. tenella (formerly P. rebeccae, named for a Bhutanese naturalist).

The third genus that must be shown is Meconopsis, and we saw seven species in total. At relatively low altitudes, M. primulina displayed typical blue flowers, but on unexpectedly short stems around 30 cm (12 in.) tall. Many before me have rhapsodised about M. bella – indeed, it is not so named for nothing. It was found growing in a variety of habitats, less of a crevice dweller than expected. Its real charm, standing up to such a hostile environment while being so delicate of scale and form, was beyond doubt. Higher up, growing in some inhospitably rocky terrain, M. bhutanica displayed sumptuous blooms some 12 cm (5 in.) across – such a shame it is monocarpic and very tricky to grow to flowering size!

There were, of course, lilies (including Notholirion), saxifrages and potentillas, Pedicularis and Corydalis, and so many others. But I will conclude with a look at just a few of the high alpines, with specialist adaptation on display. I have chosen four that epitomise the unusual plants that can be seen by braving the monsoon season at 5000 m (16,500 ft.) above sea level. Yes, it was wet at times and you may even notice the raindrops on several of the photographs! But it never rained all day, and the temperature was never very cold, and the joy of the flowers completely dominated the weather.Chionocharis hookeri is a tight hairy cushion found on high screes. The forget-me-not flowers are an exquisite blue. The giant Himalayan rhubarb, Rheum nobile, was in similar terrain. Its bracts insulate the flowers within, causing an improvement in the temperature of about 5C (9F), obviously of benefit for earlier pollination.

Saussurea gossypiphora performs a similar trick, cocooning its flowers in a cottonwool-like substance, while Eriophyton wallichii has the furriest leaves.

It isn’t cheap to visit Bhutan, but it is such a distinctive place, with such unspoiled wilderness country, that I will try to go again. Go if you can!